Proposal of a new transdisciplinary discourse method

17 Apr 2024Tags: publication

Ref: Byun, J. E. & Yi, S. R. (2024). Anti-price-gouging law is neither good nor bad in itself: a proposal of narrative numeric method for transdisciplinary social discourses. npj Natural Hazards, 1(1), 4.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-024-00005-y

Motivation

Difficulty in interdisciplinary discourses

It has been long recognised that interdisciplinary efforts are mandatory to tackle the most difficult topics of our society. Such joint efforts however remain challenging as modern disciplines have increasingly become sophisticated, obscuring cross-discipline discussions. Discussions become even more complicated when emotional campaigns are involved, which is often the case.

Re-thinking about the purpose of debates

Reading insightful references on classic social debates (e.g. The righteous mind by Jonathan Haidt and Justice by Michael Sandel), we’ve come to the conclusion that there is no universal truth, and a debate should aim to draw a an agreeable compromise to (hopefully) all stakeholder groups. This requires weighing conflicting forces between counterarguments, which we believe are all bound to be true.

As engineers, we thought computational simulation tool could be a solution.

Investigation of effectiveness of anti-price-gouging laws

Investigation

We picked up a controversial topic, anti-price-gouging laws, whose legitimacy has been heatedly debated (a good summary is available in Justice by Michael Sandel). Anti-price-gouging laws have been introduced in multiple countries to prevent sellers from raising prices higher than what is considered reasonable.

All arguments for and against the laws seem legitimate and aim for the same goal to expedite recovery with least impacts on affected people:

- Arguments favouring the laws include

- Increased prices exacerbate already affected people.

- A price cap suppresses price-gouging behaviours.

- Presence of the laws shows the authorities’ support for social justice and thereby promotes just behaviours.

- Arguments against the laws include

- A price cap hampers recovery of damaged supply lines.

- A price cap incurs hoarding behaviours.

- A price cap creates random distribution of resources, rather than by the urgency of needs.

We wondered how these make-sense forces interact with each other to determine our objectives: (i) minimise deficiency of basic goods, (ii) minimise repair duration of damaged buildings, and (iii) minimise disruptions on living standards.

For investigation, we set up a probabilistic model that simulates a post-earthquake situation including (i) building damage, (ii) affected demands and supplies, and (iii) hoarding and donation. We applied the model to San Francisco, CA, USA.

Findings

We highlight three interesting observations:

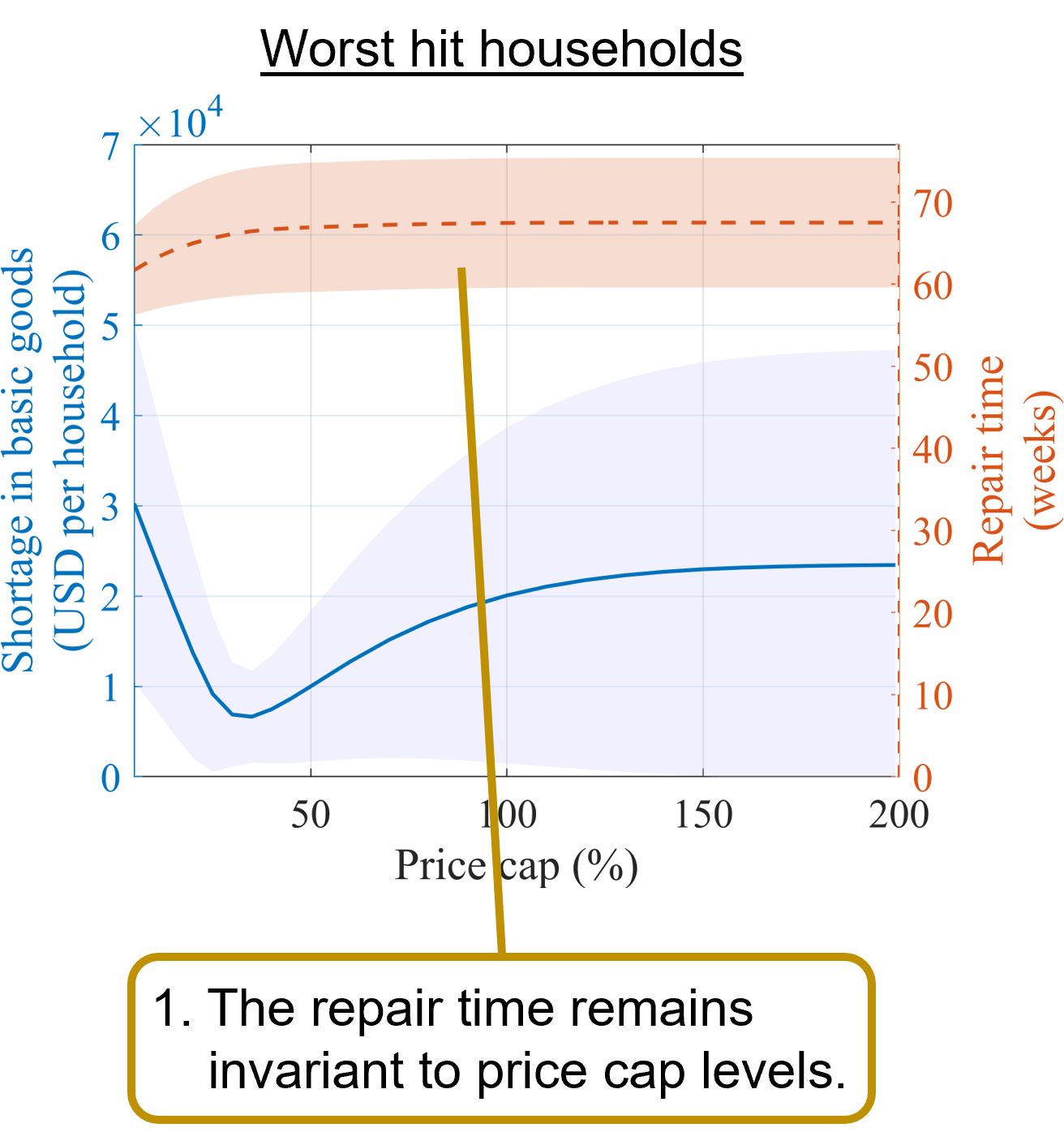

- The worst-hit households are not much affected by the level of price cap (Fig 1). This implies that they need a different support scheme.

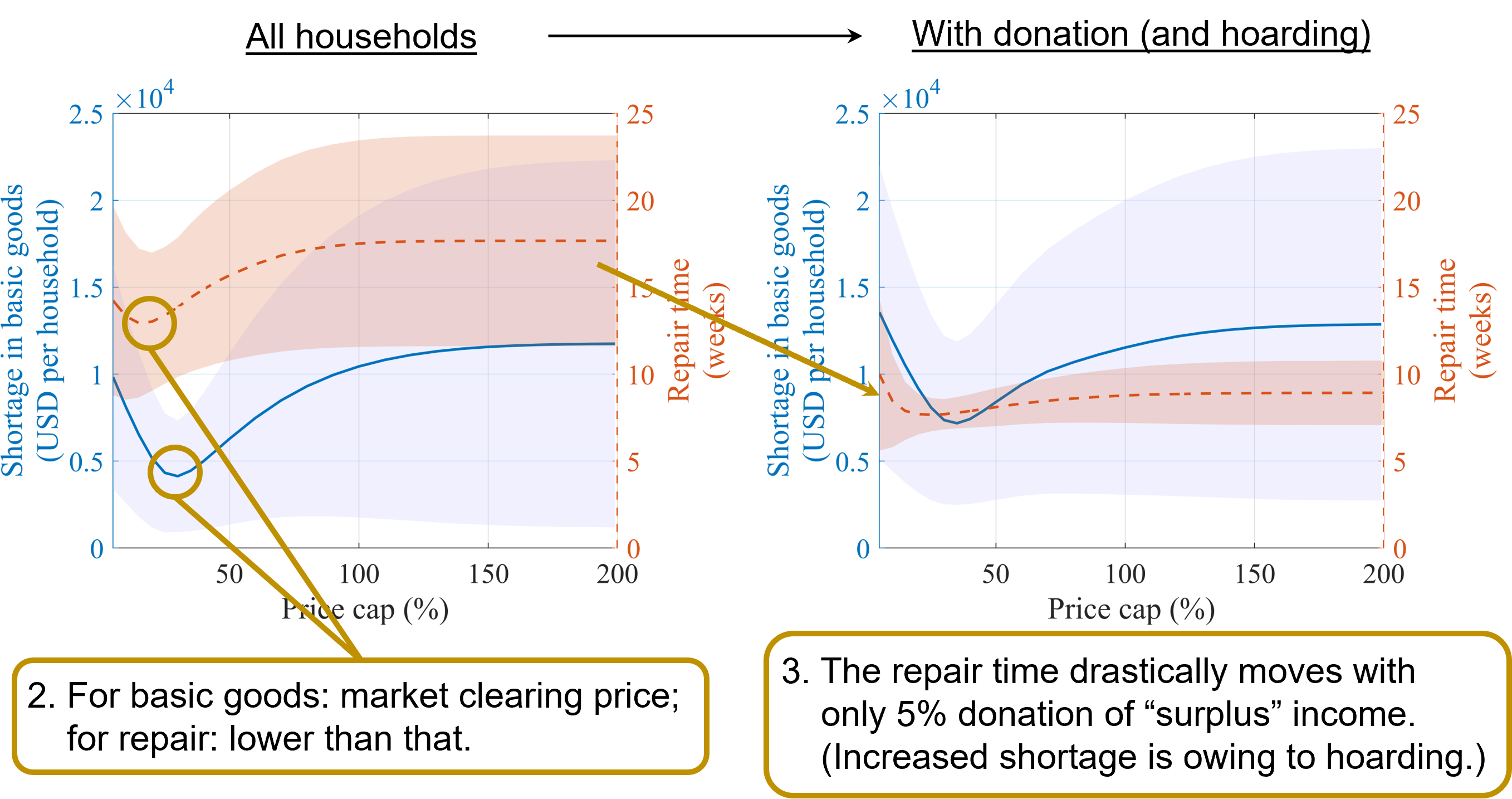

- The optimal level of a price cap is different depending on a decision objective (Left-hand side of Fig 2).

- Even a very low level of donation is significant in expediting repair durations (Right-hand side of Fig 2). This also implies that influences of the analysed arguments depend on local conditions.

A new way of having social discourse? Narrative numeric method

Motivated by the findings, we propose the narrative numeric method for transdisciplinary discourses with three purposes: (i) facilitate drawing an agreeable compromise rather than identifying the most truthful argument, (ii) facilitate iterations of discourses with more arguments added, and (iii) facilitate integration of narrative and numeric analyses. The procedure is summarised below (Table 2 in Byun and Yi (2024)):

| Step | Narrative analysis | Numerical analysis |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identify decision objectives | Define decision metrics |

| 2 | Collect candidate arguments | Define decision scenarios or decision variables |

| 3 | Identify conflicting forces | Build a probabilistic model with multiple forces |

| 4 | Reflect local conditions | Decide model parameters |

| 5 | Present evidential data | Decide/update the model or its parameters |

| 6 | Collect narrations of people | Map narrations to probability distributions of decision metrics |

| 7 | Decide acceptable social phenomena | Decide acceptable values of decision metrics |

| 8 | Draw an agreement | Select decision scenarios or a value of decision variables |

Remaining challenges

We made a wild attempt to test our idea for genuinely transdisciplinary discourses. We still find too many challenges, for example,

- what is the relationship between social solidarity and social behaviours such as price gouging, donation, and hoarding? Are they wildly different between communities?; and

- how should narratives be collected to define an acceptable level of decision metrics?

We hope this is just the beginning of our journey and have more colleagues to collaborate with. We sheepishly admit that the economic and social models in our simulation model are by our self-study…!